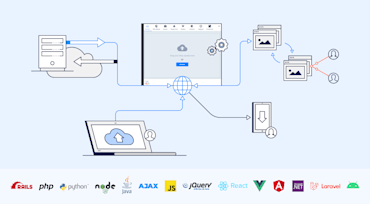

Media management is at the heart of what WordPress does, and with Cloudinary’s WordPress Plugin, we’re all set to alleviate numerous pain points for WordPress users by adapting the plugin’s features developed by Cloudinary, and adapted by XWP, on its platform into a working WordPress plugin.

Early this year, we at Cloudinary decided to go all in and build something bigger and better than what we’d built before. The team kept its word: Cloudinary’s WordPress Plugin Version 3.0—called WP Plugin V3 in the rest of this post—is here and it’s awesome!

As computer users, we constantly upload files, transferring them from one system to another over a network. You can perform uploads on a terminal, such as through the SSH File Transfer Protocol (SFTP) or Secure Copy Protocol (SCP), File Transfer Protocol (FTP) clients, or web browsers. Generally, you upload files to move data to a server or a managed service like cloud storage, but you can also send files between distributed clients.

WordPress powers 34% of the internet and represents 60% of all CMS-built sites. From small blogs to large enterprise websites, WordPress is a popular choice for publishers and companies of all kinds. Media management within WordPress is an important component and one that, when done right, can significantly boost user engagement and overall site performance.

Every image is unique, so are website visitors. In a perfect world, we would adapt images to be "just right" for all users, i.e., perfectly cropped with responsive dimensions, correct encoding settings, and optimal quality in the most suitable format.

See this example of a photo of a cat:

With the advent of technology and the attendant fast-growing demand for feature-rich computing devices (laptops, smartphones, iPads), their manufacturers are rising to the occasion by producing high-resolution machines with screens of various sizes and device-pixel ratios. Thus was born the impetus behind the need for and creation of WordPress responsive images, which automatically optimize their online display according to the size and resolution of the device screen, ensuring sharpness and crispness—a delightful user experience.

Typically, with Cloudinary, you want to do two complementary things for a remarkable user experience: save bandwidth and load your site as fast as possible because the smaller the sizes of the resources, the faster your site loads. And it’s been proven time and again that the longer your site takes to load, the smaller the number of visitors who will return. No matter whether you’re a developer or content creator, you will find Cloudinary’s tools that optimize digital media (aka digital assets) simple, intuitive, and effective.

Part 1 of this series introduces the Free Lossy Image Format (FUIF), which I recently developed. Part 2 explains the why, what, and how of FUIF. This post, part 3 of the series, delves into how FUIF is legacy friendly, which I alluded to in Part 2.

In my last post, I introduced FUIF, a new, free, and universal image format I’ve created. In this post and other follow-up pieces, I will explain the why, what, and how of FUIF.

Even though JPEG is still the most widely-used image file format on the web, it has limitations, especially the subset of the format that has been implemented in browsers and that has, therefore, become the de facto standard. Because JPEG has a relatively verbose header, it cannot be used (at least not as is) for low-quality image placeholders (LQIP), for which you need a budget of a few hundred bytes. JPEG cannot encode alpha channels (transparency); it is restricted to 8 bits per channel; and its entropy coding is no longer state of the art. Also, JPEG is not fully “responsive by design.” There is no easy way to find a file’s truncation offsets and it is limited to a 1:8 downscale (the DC coefficients). If you want to use the same file for an 8K UHD display (7,680 pixels wide) and for a smart watch (320 pixels wide), 1:8 is not enough. And finally, JPEG does not work well with nonphotographic images and cannot do fully lossless compression.

I've been working to create a new image format, which I'm calling FUIF, or Free Universal Image Format. That’s a rather pretentious name, I know. But I couldn’t call it the Free Lossy Image Format (FLIF) because that acronym is not available any more (see below) and FUIF can do lossless, too, so it wouldn’t be accurate either.